Behind The Glass Volume II - Page 1

Behind The Glass Volume II

Behind the Glass, Volume II by Howard Massey presents another prime collection of firsthand interviews with the world's top record producers and engineers, sharing their creative secrets and hit-making techniques - from the practical to the artistic. In these pages you'll find the interview with Larry.

If you prefer to have the full article in PDF-format,

download it here: Behind The Glass Volume II.

1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 Next

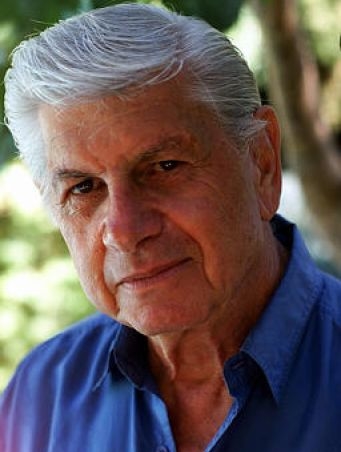

Larry Levine

The Wall of Sound Deconstructed

He was making hit records long before most of us were born. Together with a legendary producer, he fashioned a distinctive sound that was to dominate the industry for decades and inspire countless musicians and producers (including a young genius by the name of Brian Wilson) to creative excellence in the recording studio.

His name is not nearly as recognizable as Phil Spector’s, but Larry Levine was arguably just as responsible for what became known as the Wall of Sound. Born in 1928 in New York, Levine spent most of his life in Los Angeles. Shortly after returning home from service in the Korean War, he took a job at his cousin Stan Ross’s fledgling Gold Star studio in Hollywood. “At the time, Stan couldn’t afford to hire anyone, which is how I got the job,” Levine recalls with a laugh. “Because I wasn’t married at the time, I’d hang around the studio in the evening because there were always some show people there, and they were fun to be around. Then when things started getting busy, they asked me to work there. They really couldn’t pay me anything, but I was able to do on-the-job training under the GI Bill, so I earned enough to live on... barely.”

By the mid-1950s, Levine was an established engineer at Gold Star, recording many of Eddie Cochran’s greatest hits, including “Summertime Blues” and “Twenty Flight Rock.” A few years later, Spector began working at the studio, initially with Ross, then with Levine. The two of them made for an unlikely partnership—Spector was a fast-talking, eccentric producer barely out of his teens, while the soft-spoken Levine was by then a veteran of the Hollywood scene—but they would work together for more than two decades, crafting a unique sonic signature that no one else has been able to duplicate to this very day. Their hits included The Crystals’ “He’s A Rebel,” “Da Doo Ron Ron,” and “Then He Kissed Me,” as well as Darlene Love’s “Chapel of Love” and The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” and “Walking In The Rain.” In the mid-1960s, the pair shaped two of the greatest R&B hits of all time—the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” and “Unchained Melody”—and in 1966 raised the bar further still with Ike and Tina Turner’s legendary album River Deep, Mountain High, a release that only garnered limited commercial success at the time but is now considered to be one of the greatest recording masterpieces of all time.

Though he worked extensively with Phil Spector, Levine also engineered outside projects, including multiple albums with Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass (including the hit “A Taste of Honey,” which netted Levine a Grammy for Best Engineered Recording); he also worked closely for a period with Spector disciple Brian Wilson, participating in “Good Vibrations” and the legendary Pet Sounds album. As his career wound down in the early 1980s, Levine began the important work of passing the torch on to the next generation of engineers, getting involved in one of the earliest training programs launched at A&M studios. “I was fortunate enough to be able to get into the business without any training, so I always felt I should do all I could to open the door for other people,” Levine says.

It’s a statement that cogently summarizes the giving attitude of Larry Levine, one of the nicest and warmest gentlemen ever to grace a recording studio. Sadly, Larry passed away on his eightieth birthday, just a few months after giving this extensive interview in which he deconstructs the Wall of Sound for the next generation of engineers. It seems like such a fitting gift from a man whose legacy will stretch far beyond the hits he helped create.

How important do you feel training is in becoming a good engineer?

Well, I think the term “training” is kind of a misnomer in this industry, because every studio is different and every console is different. To me, being an engineer is at least eighty-five percent creative and fifteen percent technical. You really don’t need any more technical knowledge than that; it’s just a matter of knowing what button to push. Once you learn signal flow, it’s really a matter of, what do you hear?

It seems to me that you either have this magic ingredient that allows you to be a good engineer, or you don’t; I don’t think it’s something that can be evolved. When I was involved in that apprenticeship program at A&M, I could usually tell within a week whether someone had that certain something. Frankly, though, I’ve found that those people who have the makings of being good engineers often don’t do as good a job in the mundane aspects like setting up a studio as those who don’t have that capability; it’s almost as if they weren’t cut out for the job.

1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 Next

Webmaster: Jos Megroedt | Website: http://www.josmegroedt.com/ |

This site is hosted by: http://www.hostingphotography.com/