Times Online Obituary

From The Times

May 17, 2008

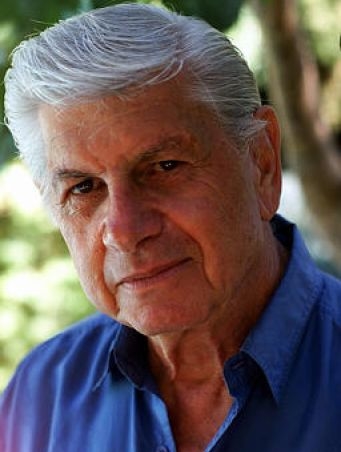

Larry Levine

Recording engineer who helped the producer Phil Spector create his hit-making ‘wall of sound’

Whatever the psychology behind Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” on such records as Be My Baby and You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’, his obsessions depended upon coolly diligent Larry Levine. An engineer a dozen years Spector’s senior, he enabled a small, low, hot Los Angeles studio’s acoustics to turn massed instruments and vocalists into something that leapt from humble radio speakers worldwide. “Larry’s a nice fellow, really sweet,” said Spector, who worked with him again, less equably, in the Seventies.

Born in New York in 1928, Levine was brought up in Los Angeles. Army service in Korea as a radio operator led to the aviation industry, but more congenial were evenings at a recording studio — Gold Star on Santa Monica Boulevard and Vine Street — owned by Stan Ross and Dave Gold. He became assistant to Ross (who recorded the teenage Spector’s first band, the Teddy Bears, on To Know Him is to Love Him (1958). Soon an engineer himself, Levine supervised Eddie Cochran — including the stuttering, echoing Summertime Blues while Toni Fischer’s The Big Hurt was overdubbed upon itself at a different speed to an accidental, notable effect.

The city had an array of session musicians — some, such as Glen Campbell, Dr John and Leon Russell, later famous in their own right, as was Herb Alpert, with whom Levine created the Tijuana Brass discs. In 1962, after a New York sojurn, Spector returned to the West Coast to a studio with laid-back musicians that he relished.

With a Gene Pitney song, He’s a Rebel, and lead vocalist Darlene Love standing in for the Crystals, Spector was disgruntled at being allocated Levine as engineer while Ross was in Hawaii. He soon realised that he was a literal sounding-board; Levine’s first impression, however, was of “something abrasive there. It wasn’t anything he said. It was just an aura.” But with the musicians at work, Spector showed his charm and knowledge, insistent that the pianist Al DeLory’s doodle should open the song, the off-beat vocal a happy mistake — a number one hit.

His record label established, there came the profoundly odd Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah, from Disney’s Song of the South. As credited to Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans, the instruments, including three pianos, shot Levine’s meters into the red. With this the required sound, Spector stopped him from turning them off, and Levine delighted in catching Billy Strange’s guitar solo through others’ microphones. Not Spector’s most popular disc, this second lucky accident was as sexually charged as Be My Baby. Cool, gangling Levine and Spector, the diminutive, explosive producer, had found an unlikely rapport.

With session musicians happy for overtime, Spector and Levine spent hours in getting the right sound before attempting any recorded takes; guitarists endlessly repeated simple chords as Spector, eschewing overdubs (but for vocals), worked out how to meld them with everything else. Levine said that the result “didn’t in any way duplicate what you heard in the studio. It was just exciting and thrilling and full-bodied. The musicians would come into the control room for the playback and just be blown away. They simply couldn’t believe that what they were hearing was what they’d been playing.”

Hits followed swiftly, two peaks being the Ronettes’ Be My Baby, an ordinary song made powerful, and, best, the Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’, Levine’s favourite, Spector’s subtlest — his jazz roots evident in Carol Kaye’s bass and Barney Kessel’s guitar.

Levine, able to discuss many subjects with Spector, persuaded him to cut back the unctuous Silent Night monologue on the Christmas album, and later conceded that the technology could not quite capture River Deep, Mountain High for whose fevered vocal session Tina Turner stripped to her bra — “What a body,” noted Levine.

With River Deep a flop in the US, Spector quit for several years while Levine was asked by Herb Alpert to work at his label A&M, which Spector briefly joined in 1969 before work with John Lennon and George Harrison. He and Levine were reunited for Leonard Cohen’s underrated Death of a Ladies’ Man (1977) whose sessions found Spector changed. Levine said: “It was the booze. When Phil started drinking, he was out of his head. That was not Phil. That’s not the Phil I knew.” In 1979 they worked, even more surprisingly, with the Ramones for the group’s best-sounding album, End of the Century. A protracted process, this may have contributed to the heavy-smoker Levine’s heart attack. Distraught, Spector could not visit him, and they were out of touch until he asked Levine to remaster the Sixties sides for CD. The amiable Levine, meanwhile, had left music to sell houses in Beverly Hills but was duly fired, his boss disgruntled when a purchaser admiringly told him that Levine was more interested in his, the purchaser’s, welfare than the boss’s.

For all the turbulence, Levine felt close to Spector, of whom he often spoke after Spector’s arrest on a murder charge — and regretted that tape degeneration made CD transfers lack the impact of the original.

Levine died on his 80th birthday and is survived by his wife and three sons.

Larry Levine, recording engineer, was born May 8, 1928. He died May 8 2008, aged 80

Webmaster: Jos Megroedt | Website: http://www.josmegroedt.com/ |

This site is hosted by: http://www.hostingphotography.com/