The Independent Obituary

Tuesday, 13 May 2008

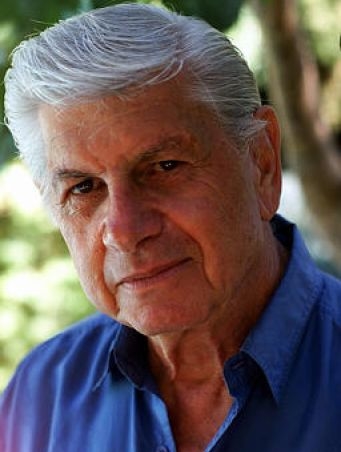

Larry Levine: Gold Star recording engineer who played a crucial role in the building of Phil Spector's 'Wall of Sound'

The recording engineer is the producer's right-hand man, there to help capture a performance from the musicians and singers and mix all the elements into a coherent, cohesive whole, and it was in this crucial role that Larry Levine helped the legendary Phil Spector build his "Wall of Sound" in the Sixties.

Levine's excellence in his field was recognised when he won a Grammy award for Best Engineered Recording for "A Taste of Honey", the 1965 hit single by Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass (the instrumental also triumphed in the Record of the Year and Best Pop Arrangement categories). Indeed, Levine made such a contribution to the trumpeter's multi-million selling albums that he was often called the eighth member of the Tijuana Brass. He also worked with Brian Wilson on the making of Pet Sounds, the classic 1966 album by the Beach Boys.

Although he is forever associated with Gold Star Recording Studios in Los Angeles, Levine also worked at A&M Studios in Hollywood in the Seventies, where in 1973 he engineered the Quincy Jones album You've Got It Bad Girl and the soundtrack by Burt Bacharach and Hal David for the ill-fated musical remake of Lost Horizon.

Levine was in his early twenties when he joined Gold Star, the studio founded by his cousin Stan Ross and Dave Gold in 1952. Levine learned fast and, by 1956, when the studio added a second room, he was one of the house engineers recording Eddie Cochran. "That started out as Eddie recording demos for the American Music publishing company and evolved into us working on all of his hit records," Levine recalled. He helped the rock'n'roller make "Twenty Flight Rock", "Summertime Blues", "C'mon Everybody", "Somethin' Else" and "Three Steps to Heaven", which topped the British charts after Cochran's death in April 1960.

Levine first met Phil Spector in July 1958, when Spector was a member of the Teddy Bears, whose US chart-topper "To Know Him is to Love Him" was engineered by Ross at Gold Star. "I didn't take to him at all, which is not unusual, I understand," Levine said later. "There was a little acerbic attitude." But they began forging a working partnership in July 1962 when Spector came to record "He's a Rebel", the third single by the Crystals, at Gold Star. Since Ross was away, Levine did the session and a subsequent one for Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans' "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" three weeks later.

"It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me," he said.

After we recorded "Zip-A-Dee" in one take and then added the voices, I did my mix of the voices against the track and I know I started it off with the voices a little too low. Then I wanted to make another mix with the voices a little higher, but Phil said, "No, that's good", and that was it. Everything was done in one mix.

Levine was particularly proud of this session and played the Bob B. Soxx track to so many industry insiders that Spector had to rush-release it as the next single on his Philles label, the "follow-up" to the US number one "He's a Rebel".

"From that point on, I was Phil's engineer," Levine said. He had clashed with Spector over his tendency to overload the mixing desk, but developed a keen understanding for what was required: Phil knew what he was looking for and could communicate this. I think the biggest part I played was to serve as his sounding board. He trusted me, that was the thing. Phil wanted everything mono but he'd keep turning the volume up in the control room. So, what I did was record the same thing on two of the [Ampex machine's] three tracks just to reinforce the sound, and then I would erase one of those and replace it with the voice.

Along with the arranger Jack Nitzsche and the session musicians who became known as the Wrecking Crew – the drummers Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer, bassists Carole Kaye and Larry Knechtal, guitarists Barney Kessel, Tommy Tedesco and Bill Strange and the pianist Leon Russell – Levine became a central component of the team the diminutive producer assembled to fashion such epochal recordings as the Crystals' "Da Doo Ron Ron", the Ronettes' "Be My Baby", the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin" and Ike and Tina Turner's "River Deep, Mountain High".

Since Spector insisted on having two, three or even four of everything – pianos, guitars, percussion, reeds – to create his "little symphonies for the kids", Gold Star was rather cramped and the absence of air-conditioning added to the intense atmosphere, but Levine somehow kept cool under pressure as the perfectionist Spector tried to conjure up the sound he heard in his head. "I found out that the more people you put in the room, the better the sound is," said the engineer. "The bodies provide dampening." Levine would only start rolling tape when everything was to the producer's satisfaction, sometimes after 40 run-throughs, and added just the right amount of echo when prompted.

Spector "was always trying to create more and more," according to Levine: I think it finally ate him up at the end, because the technology was not able to keep up with him. Probably "River Deep, Mountain High" should have been greater than "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin", but it wasn't. He tried to go beyond the scope of what we could do technically.

Spector's behaviour grew increasingly eccentric and erratic but Levine worked with him again in the Seventies, most notably on Death of a Ladies Man, Leonard Cohen's 1977 album and the Ramones' End of the Century in 1979. The engineer confirmed stories of the producer pulling a gun on both Cohen and the Ramones, and also recalled arguing with Spector on the occasions he turned up drunk in the control room. "We weren't getting anything done; I reprimanded him," Levine said in a CNN interview a few weeks after the actress Lana Clarkson was found shot dead at Spector's house in 2003 (the case against Spector is ongoing). "I kind of had a relationship of an older brother to him that I'm sure he respected. When I didn't approve of his actions, he would get rebellious even more."

An affable man with an excellent memory, Levine relished being interviewed about his work with Wilson, Alpert and especially Spector. "For me, it was amazing to hear things from the outset, starting with the guitars and gradually building up to the 'Wall of Sound'," he said. "That was a unique experience."

Pierre Perrone

Larry Levine, recording engineer: born Los Angeles 8 May 1928; married 1955 Lyn Spivak (two sons); died Los Angeles 8 May 2008.

Webmaster: Jos Megroedt | Website: http://www.josmegroedt.com/ |

This site is hosted by: http://www.hostingphotography.com/