The sound of LA

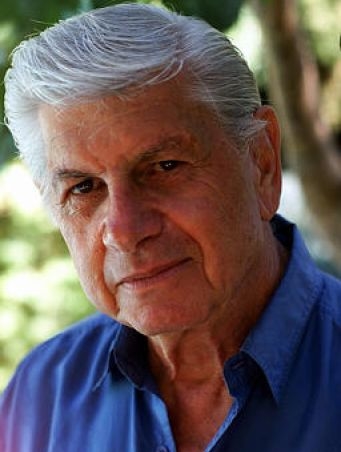

Larry Levine

The Sound of LA

Recording engineer who was Phil Spector's righthand man during the Wall of Sound era

Friday 6 June 2008 19.07 EDT First published in The Gardian on Friday 6 June 2008

If Phil Spector was the architect of the Wall of Sound, Larry Levine was the bricklayer. Spector's records were created in the studio, and had no life outside the grooves of a seven-inch 45rpm single. Levine, who has died at the age of 80, was Spector's studio engineer during the brief golden age that ran from the Crystals' He's a Rebel in 1962 through the Ronettes' Be My Baby and the Righteous Brothers' You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' to Ike and Tina Turner's River Deep - Mountain High in 1966. It was he who devised the techniques that allowed the brilliant young producer to turn the sounds in his head into Top 40 masterpieces.

There are bootleg recordings of the whole elaborate and infinitely painstaking process whereby Spector and Levine would subject dozens of musicians and singers to every trick of recording technology in order to create the celebrated "little symphonies for the kids". The Crystals' Da Doo Ron Ron is among those tracks whose gestation has been preserved. As the session continues, Spector can be heard ensuring that the tempo is exactly right and that the dynamics rise and fall exactly in accordance with his wishes. His interjections are constant, admonishing the pianists or telling the drummer to move his snare two inches to the left. Time and again his voice breaks through on the talkback microphone, halting a take. "No!" he shouts. "Nothing happened! Nothing happened! It's supposed to be 'one two three Da doo ron BAAAAAHH!' What happened? One guy played it right and one guy played it wrong!" And from behind the mixing desk, the patient voice of Levine comes through: "Take 25 ... "

Among Spector's favourite techniques was the lavish use of echo, which he slathered over everything to blur the distinctions between individual instruments, making the finished record sound even bigger. Levine was the one who explored the many possibilities of various forms of echo, before presenting them for the producer's use.

Born in New York, Levine grew up in Los Angeles and served in the US army during the Korean war. After demobilisation, he began working for his cousin, Stan Ross, the co-owner of a Hollywood recording studio called Gold Star. Located at 6252 Santa Monica Boulevard, near the corner of Vine Street, the studio had quickly become famous for its concrete-lined echo chambers, designed by Ross's partner, David Gold. Eddie Cochran's big hits - C'mon Everybody, Summertime Blues and Three Steps to Heaven - were recorded there, with Levine assisting, between 1958 and the singer's death in 1960. And when Spector grew tired of the cynicism of New York's session musicians and relocated to Los Angeles, he headed for Gold Star.

For his first session for his Philles record label in Hollywood, on July 13 1962, he scheduled a song by Gene Pitney called He's a Rebel. Spector had expected Ross to be the engineer, and was disconcerted to discover that he was on holiday and Levine had been assigned to the session instead. "When I walked into a session of that magnitude, I was a little nervous," Levine said a few years later. "I thought I was going to blow it. I was a little frightened by the new sound, and I didn't get a good feeling from Phil. He looked like a creepy kid to me. But eventually we worked up an understanding."

Spector discovered that, like the LA musicians, the young engineer was not contemptuous of music aimed at teenagers and was unafraid to experiment with sound. "You really needed somebody good alongside of you," Spector remembered, "and Larry was really helpful. In those days, for what I was doing, he was invaluable. We were breaking every rule there was to break." After He's a Rebel, Levine engineered every record Spector made for the next eight years.

The brief golden age closed with the commercial failure of River Deep - Mountain High, possibly as a result of distributors and disc jockeys taking a covert reprisal against what they saw as Spector's arrogance. It put an end to Philles records, but not to the partnership between Spector and Levine. The latter had already enhanced his reputation by working with Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass, winning a Grammy for his contribution to their hit version of A Taste of Honey, and when Alpert formed his own label, A&M, he invited Levine to be their staff engineer. When Spector produced a group called the Checkmates Ltd for A&M in 1969, the two men were reunited.

"Phil can do anything if he wants to do it bad enough," Levine said around that time, "but I don't think he's hungry enough to try hard now. He got hung up on the image that was built around him. But if he ever wants to, he can make it back again."

Such optimism was misplaced. Although they were to collaborate again, first in 1977 on Leonard Cohen's unfairly maligned Death of a Ladies' Man and then in 1980 on the Ramones' End of the Century, both sessions were disrupted when an increasingly unstable Spector pulled a gun in the studio. And, in any case, the Wall of Sound was already a museum piece.

Levine, who leaves a widow, Lyn, and three sons, Rick, Rob and Mike, died at his home in Encino, California, on his 80th birthday.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When Larry died, over 130,000 links reported his death.

Webmaster: Jos Megroedt | Website: http://www.josmegroedt.com/ |

This site is hosted by: http://www.hostingphotography.com/